Seismocardiography (SCG): A “Seismograph” for the Heart

Author: Michal Barodkin

Seismocardiography (SCG) is a non-invasive method of recording the subtle vibrations of the chest wall caused by the heart’s mechanical activity.

In simple terms, it’s like placing a miniature seismograph on a patient’s chest to “feel” each heartbeat – similar to how a seismograph detects earthquakes.

While an electrocardiogram (ECG) measures the heart’s electrical signals, SCG measures the heart’s mechanical movements: the actual thumps, pumps, and valve motions that occur with each beat.

How SCG Works and Its Relation to ECG

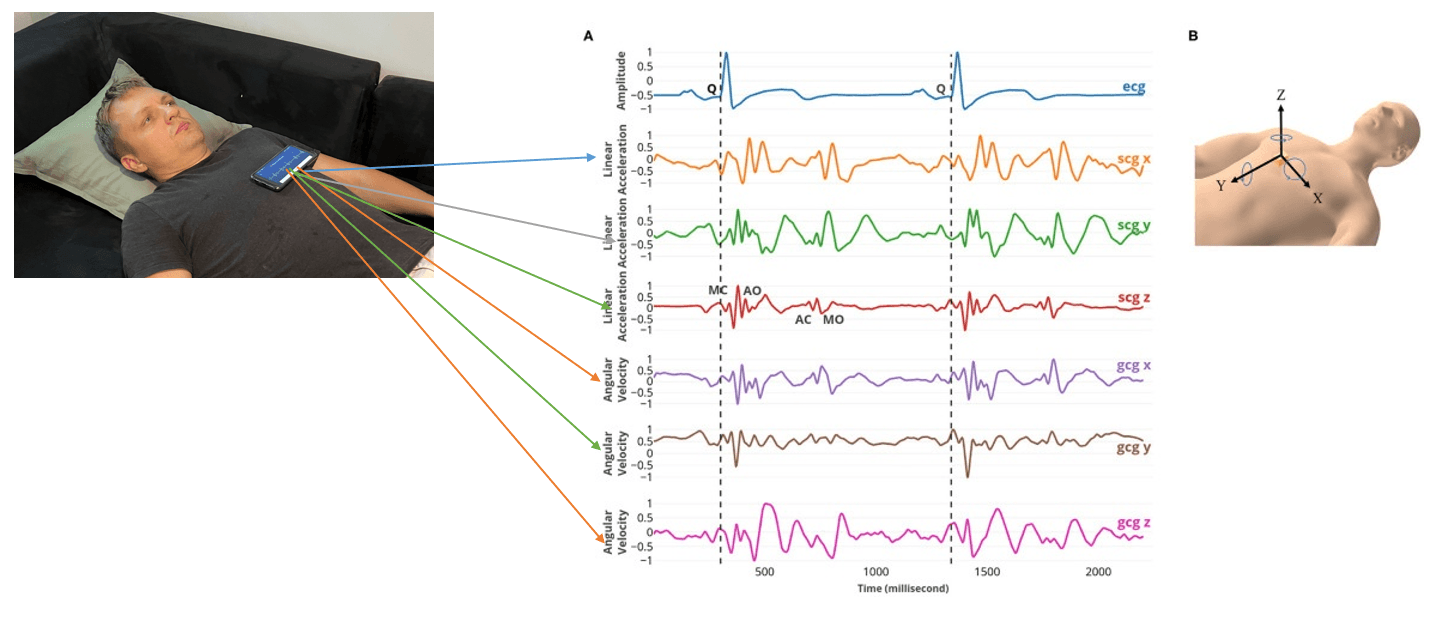

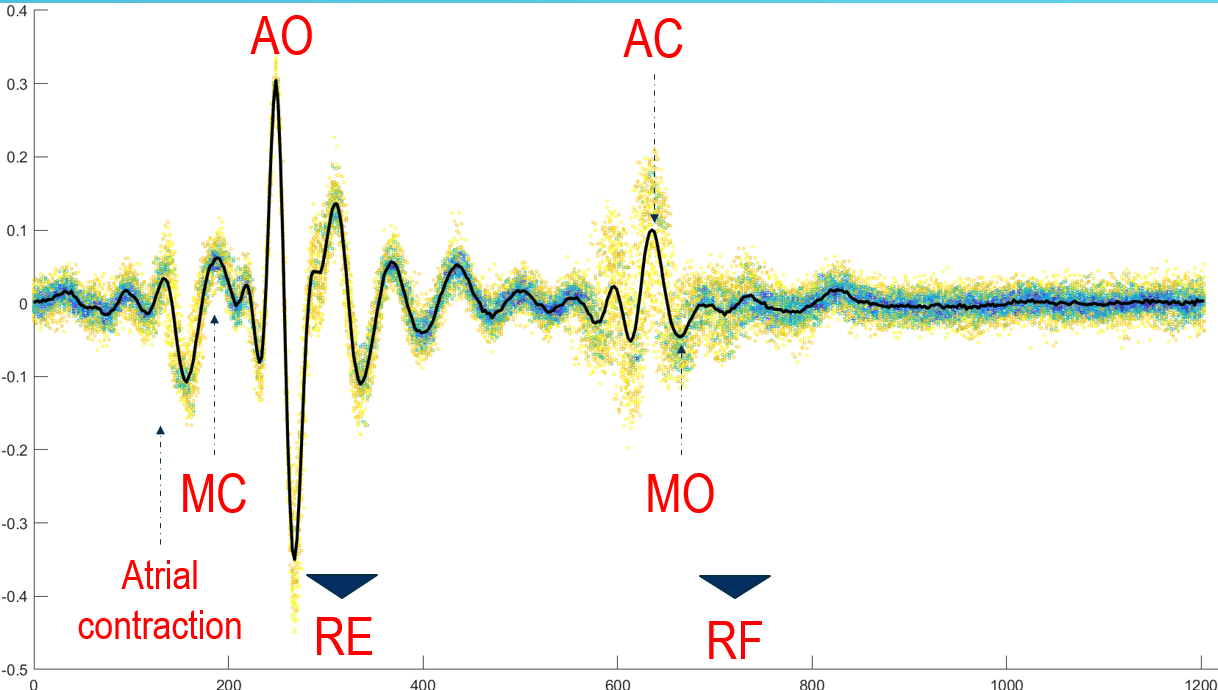

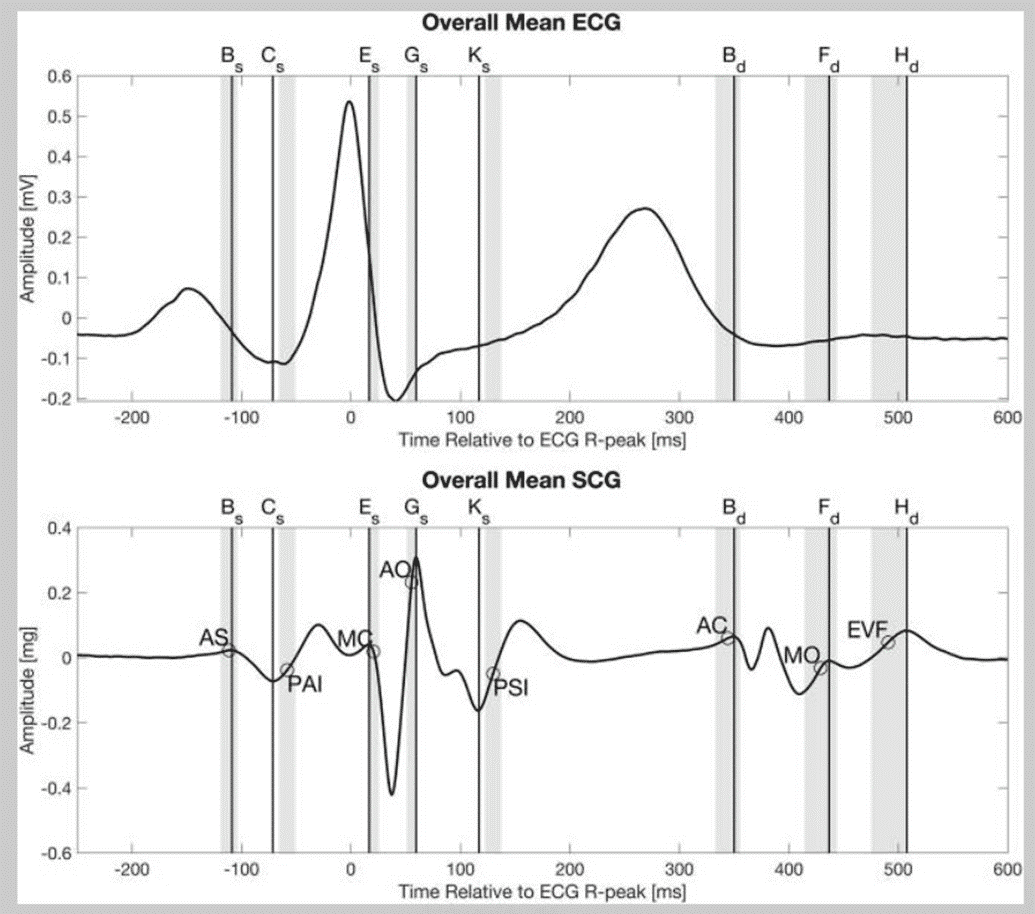

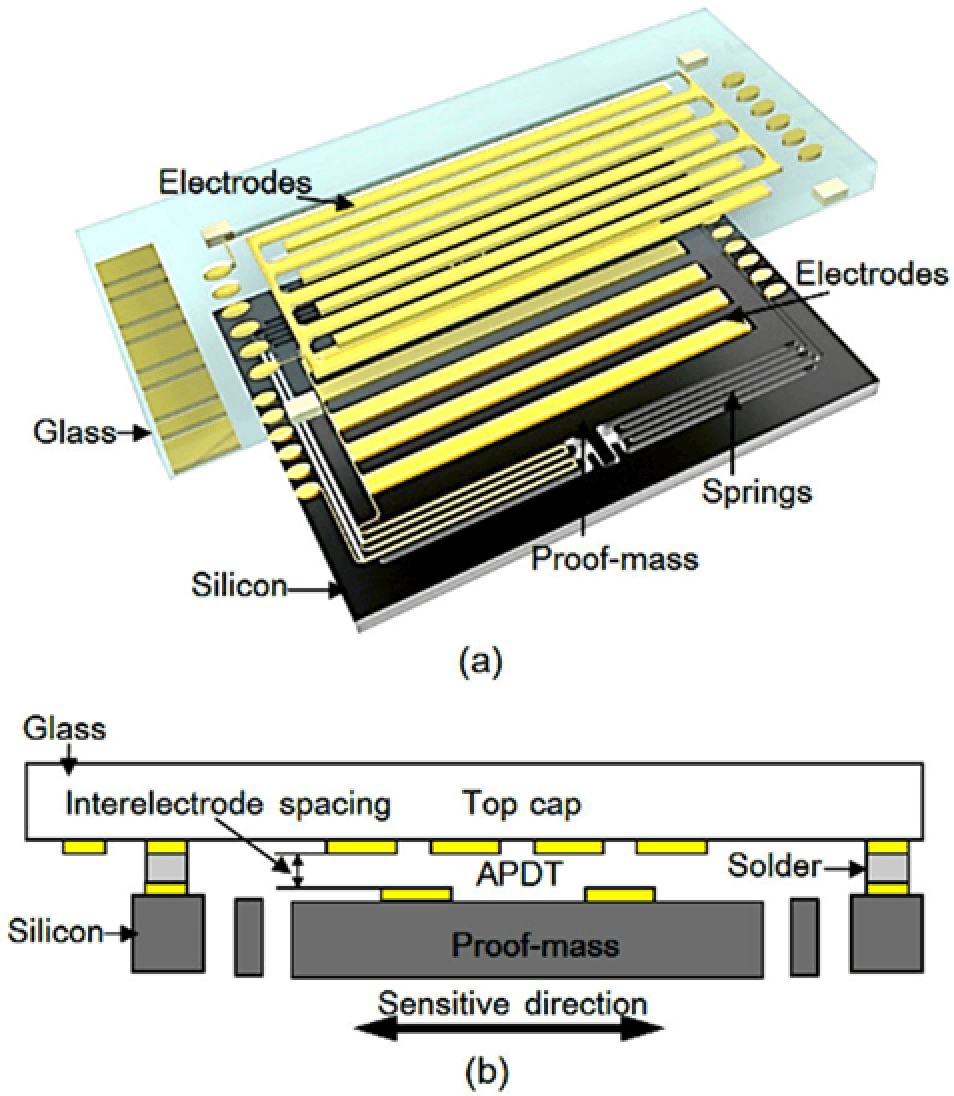

To record an SCG, a sensitive accelerometer or sensor is attached to the chest (for example, on the sternum) to detect tiny motions with each cardiac cycle. Every heartbeat generates a characteristic SCG waveform – a series of waves and peaks corresponding to events like the heart’s contraction and the opening/closing of valves.

For instance, as the left ventricle contracts and blood is ejected, the chest vibration produces a prominent spike, and valve closures produce other smaller waves. These mechanical events happen in concert with the electrical events seen on ECG.

In fact, the rhythm of the SCG waveform mirrors the rhythm of the ECG: each ECG R-wave (the electrical ventricular contraction signal) aligns with a burst of mechanical vibration in the SCG. Thus, a normal heartbeat produces both an ECG complex and a synchronized SCG “thump.”

SCG vs. ECG: It’s important to understand that SCG and ECG are complementary. The ECG excels at depicting the heart’s electrical conduction and is the gold standard for diagnosing arrhythmias (abnormal heart rhythms). SCG, on the other hand, provides insight into the actual pump performance of the heart – how forcefully and synchronously the heart is contracting.

For example, ECG will show if a signal is blocked or premature, while SCG can show whether that electrical disturbance translated into a weaker heartbeat or delayed blood flow. Because SCG measures what the heart muscle does, it can reveal things like valve dysfunction or pumping inefficiency that might not be obvious on ECG.

In practice, SCG is often recorded simultaneously with ECG, allowing doctors to correlate electrical and mechanical events beat by beat.

Studies have shown that adding SCG to routine tests can improve detection of heart problems – one early study found that combining exercise ECG with SCG improved detection of coronary heart disease significantly (from ~70% to ~88% in that trial).

From a technology standpoint, SCG has advanced with modern sensors. High-quality accelerometers (including those in smartphones and wearables) can capture SCG signals, meaning that one day patients might simply lie down with a small sensor or phone on their chest to record their heart’s vibrations.

This is of great interest for convenient, continuous heart monitoring, especially for catching intermittent issues like sporadic arrhythmias. In summary, SCG offers a “mechanical stethoscope” view of each heartbeat without any additional required devices or wearables.

Clinical Evidence and Further Reading

The effectiveness of Seismocardiography (SCG) is backed by a growing body of research. Modern studies leverage AI and advanced sensors to unlock new diagnostic possibilities.

AI-Powered Diagnostics

A 2023 study published in the Annals of Biomedical Engineering demonstrated that combining SCG with AI can diagnose aortic valve problems with up to 95% accuracy, rivaling advanced MRI scans. This highlights SCG's potential as a fast, affordable screening tool.

Read the study ↗Remote Heart Failure Monitoring

Presented at the American Heart Association in 2024, the SEISMIC-HF 1 study showed that a wearable SCG patch could estimate heart pressure in patients with heart failure, with accuracy comparable to invasive tests. This opens the door for better remote care and management of chronic heart conditions.

Read the study ↗For a comprehensive overview of the latest research and to explore interactive data, visit the OpenSCG project.

Explore interactive research data on OpenSCG.org ↗Our Research

Our own research, "SCG With Your Phone: Diagnosis of Rhythmic Spectrum Disorders in Field Conditions," was published on arXiv and forms the basis of our deep learning framework.

Read the full paper on arXiv:2601.13926 ↗

Ready to read SCG waveforms? See our clinical pattern guide →